COINS uses a centralized PostgreSQL database. We have been so busy developing new features that we have not upgraded the database used by the COINS production application since 2010!

New feature requirements and a need for increased disk space on our production server are finally motivating us to upgrade to PostgreSQL 9.4.

While we are at it, we will upgrade the underlying virtual host to Ubuntu Server 14.04, with enough RAM to fit our rapidly growing datbase in memory.

Finally, it makes sense to lay some ground work to clean up our inconsistent use of database names and ports.

Summary of changes:

| Current Value | New Value | |

|---|---|---|

| OS | CentOS 5.5 | Ubuntu Server 14.04 |

| DBMS | PostgreSQL 8.4.5 | PostgreSQL 9.4.2 |

| RAM | 16GB | 48GB |

| CPU Cores | 4 | 4 |

| Recovery | Nightly pg_dump | WAL archiving for PITR (managed by PG Barman |

| Replication | Daily pg_restore from nightly pg_dump | Hot Standby w/ WAL shipping |

| COINS DB name | postgres | coins |

| Port | 6117 | 5432 |

| Hostname | tesla.mind.unm.edu | proddbcoin.mind.unm.edu |

| Connection Pooling | none | pgbouncer |

Justification

Operating System

CentOS has served us well for many years, but we have found that Ubuntu’s more up-to-date repositories allow us to stay with the herd as new features are released in packages we depend on (e.g. PostgreSQL, PHP5, Node.js, etc…)

Postgres

Simple: 8.4 is no longer supported. Also, new JSON functionality is really nice (e.g. row_to_json).

RAM

When our current production database server was provisioned, 16GB was enough ram to hold two copies of the COINS database. The database is currently 24GB on disk, and growing fast. 48GB should buy us a little time.

CPU Cores

Postgres does not do anything special for multi-core environments. Instead, it relies on the operating system to destribute its child processes across the cores evenly. Our database has never been CPU bound, so we see no need to increase the number of cores at this point.

Disaster Recovery and Backups

We currently have a cron which performs a pg_dump of the production database every night, and stores the dump on our internal network storage at MRN. In the event of a total loss of our database server, we would be able to recover all changes made before midnight on the day of the failure. Utilizing WAL archiving will allow for Point in Time recovery, and could allow us to salvage data and changes made only minutes or seconds before the outage. In addition, it lays the ground work for a geographically distributed recovery system.

Replication

In order to get COINS running as soon as possible after an outage, we have another production-ready database server running at all times. This database is refreshed every morning from the previous night’s pg_dump of production. Unfortunately, if the production database were to fail, users would loose access to data entered after the last pg_dump. Further, if we were able to salvage the data entered between the last pg_dump and the outage, we would need to somehow merge all of that data with data entered into the replication database after the outage.

The new system uses WAL streaming to replicate all changes made in production (even schema changes!). In the event that the production database were to fail, the replication database would likely be only a few records behind the production database. Aside from loosing much less data in the event of a failover, there are other benefits to having a nearly up-to-date copy of production lying around at all times:

- Backups can be made of the replication database, thus reducing the load on the production server during backup times

- The replication database can be configured to handle read-only queries, further reducing the load on the master production database, and decreasing query time.

Database name

Back in 2010, the COINS team migrated from an Oracle Database to PostgreSQL. Our understanding of Postgres was still very limited, and we made some poor design decisions. One of these decisions was to use the default maintenance database as our primary DB. This does not directly cause any problems, but is generally a bad practice.

There are at least one dozen devices spread across the United States that connect to our production database, and rely on the current database name. Changing all of these touch points in a single go would be stressful and very risky (even after practice, and lots of planning, we could still miss or break a few devices). Updating the devices one at a time to utilize the new database name is therefore much more favorable. Doing so will allow us to cooperate with the device owners to come up with a time that will not negatively impact their work.

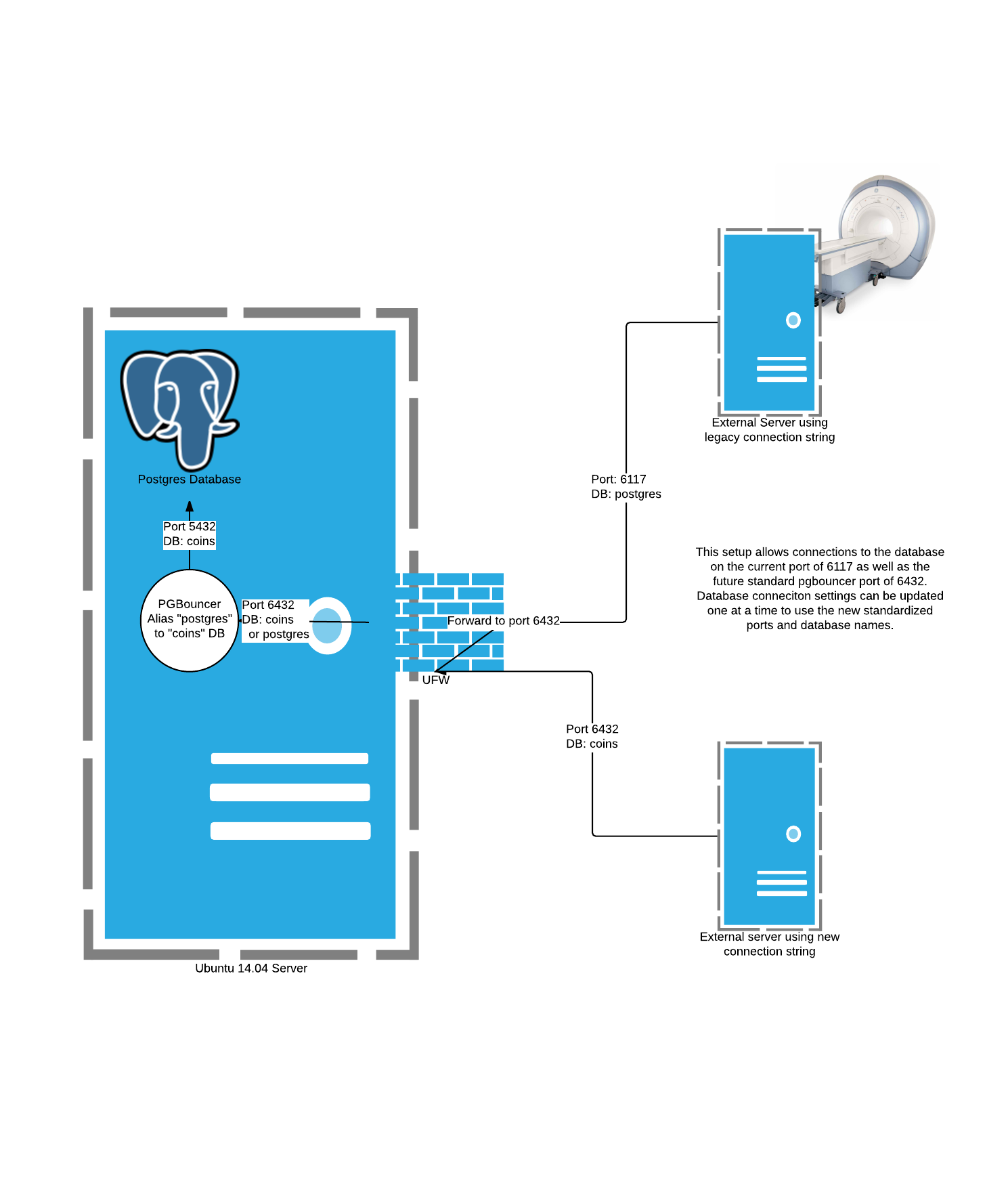

The problem is: a Postgres database can only have one name and one port. We can overcome this by using a connection pooling tool called PGBouncer. In addition to reducing the overhead involved with creating connections inside of PostgreSQL, PGBouncer also allows aliasing the database name. This means that some devices can connect to our database using the database name postgres while others can connect using the database name coins.

Database port

Another one of the poor design decisions from back in 2010 was to use a non-standard port for PG. I believe that this was a security through obscurity decision. Not only does the obscurity cause issues with our own configuration, it pprovides no additional security against anyone who is able to port-scan on our network. Any security benefit that it might have given us is void as soon as I publish this article.

Changing the port is subject to the same pitfalls mentioned above, so we need a way to support both the legacy port and the new port simultaneously while we carefully update all devices. This can be accomplished using port forwarding within the database server

Hostname

Just to be consistent with our latest server naming convention, the production database should be called proddbcoin. Since we use static IP assignments in our DNS, this should be easy: We can direct all legacy and current hostnames to the same IP, allowing us to slowly migrate devices to the new hostname. In fact, most devices uses a public IP address to connect to our database, since they are not within our private network.

Connection Pooling

I went over this a little in the database name section. The connection pooling approach prevents the overhead involved in creating a new connection each time a device, or our PHP server needs one. I also allows us to alias the database name for a smooth transition away from using the postgres database. Finally, it offers the benefits typically associated with a reverse proxy: the possibility of load ballancing across multiple servers, or switching the servers out behind the connection pool without interrupting service at all.

Summary

The new COINS production database setup may seem a bit more complex than the one it is replacing, and it is. However, all of these complex pieces are being provisioned and configured using Ansible, so the steps can easily be repeated and tweaked.

Here is a diagram showing how both old and new connections strings can reach the same databse:

The database is slated to be replaced on Wednesday, June 17th. I will be practicing the deployment using Ansible in our staging environment until then